Did you see the recent movie, Lincoln? If you did, you may have

noticed the character, Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker. As I

watched the movie, I wanted to know more about this person and how she became

the companion and friend to the first lady. I was curious… I knew Mrs. Lincoln

had a “dressmaker,” in those days White women of means had someone to make

their clothes. That was not unusual; however, I was not aware of the depth of

their employer -employee relationship.

Who was Elizabeth Keckley? How did she, working as a ‘seamstress’ or ‘dressmaker,’

come to be a close friend and companion of the first lady at of the United

States? My experience as a fashion designer fueled my interest in the life of a

Black fashion designer who had such high status at that time in American

history.

The movie was a Steven Spielberg and

Kathleen Kennedy production, and I allowed for the fact that they may have

taken some creative license; therefore, I proceeded to do my own research. I was

fascinated with the facts I uncovered, and I will share them with you.

I found a picture of Elizabeth

Keckley (Keckly) and I have to give credit to the movie makers for their realistic

casting because Gloria Reuben, who played the part, had a remarkable physical resemblance

to the real person.

Gloria Reuben as Elizabeth Keckley with Sally Fields as Mary Lincoln in the movie Lincoln.

Gloria Reuben as Elizabeth Keckley with Sally Fields as Mary Lincoln in the movie Lincoln.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley, also known as Lizzie, was born a

slave around 1818 in Dinwiddie, Virginia, although there is some speculation as

to the exact year of her birth because of the way slave records were kept. Her

parents were listed as George Pleasant and Agnes Hobbs. George Pleasant was a

slave on another plantation, and eventually was moved out of state; therefore,

Elizabeth seldom saw her father, but his love for her was unwavering as

expressed through letters over his lifetime. She would discover, as her mother

lay dying, that her actual father was her mother’s White master, Colonel

Armstead Burwell.

Although Elizabeth suffered many

tribulations as a slave, she maintained a positive attitude about the circumstances

of her life. Perceived as a beautiful woman, Elizabeth was also self-confident,

self-determined, and maintained an independent attitude which may have been the

reasons for her being brutally whipped – they were traits that her masters felt

needed to be beat out of her. She was

violated by a White man over many years; in fact, it seems that her master gave

her to his friend as a concubine. As a result of this unwilling relationship,

in 1839 Elizabeth gave birth to a son, George. Despite all of these emotional upheavals

in the merciless, ruthless, and inhumane atmosphere of the slave environment,

Elizabeth credited her personal strength to her experiences while being a

slave.

Elizabeth

established herself as a valuable dressmaker and built a clientele of wealthy

high society women. In fact, during a two year period she was able to make

enough money through her sewing skills to support her money-strapped master’s

family.

Her master moved to St. Louis where Elizabeth

met and married James Keckley; however, it was a short marriage – some have

expressed the belief that her independent attitude got in the way of the

relationship. Elizabeth Keckley was born ahead of the formal women’s rights

movement, but she had an affinity to the cause.

In November of 1855, with loans from her

wealthy clientele, Elizabeth was able to pay $1, 200 to purchase her own freedom.

She had used her networking skills to build a viable business, and respect for

her dressmaking/ design talent was appreciated through the social circles. By

1860, she had moved to Washington, D.C. and attracted the attention of the

wives of the elite: Mrs. Jefferson Davis, Mrs. Robert E. Lee, Stephen Douglas,

and of course Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. It was a known fact that before the civil

war, confident that the South would win, Mrs. Davis offered to take Elizabeth

home with as her personal designer. Elizabeth turned down the offer and chose

to stay with the North.

This woman, born a slave, eventually had 20

employees, and was recognized in the exclusive society for her expertise in fit

and design. She became a constant companion to Mary Todd, she was with the

family: when Lincoln gave the Gettysburg Address; at fundraising events for the

civil war efforts; when the Lincoln’s lost their son to typhoid in February, 1862

- even though her own son had been killed in the Civil War (George had enlisted

as a white man) in August of 1861; to comfort after the president Lincoln's assassination;

to personally help Mary Lincoln sell garments to help raise money when the

first lady was struggling financially.

In 1868 Keckley wrote a memoir that

would be the unwitting cause for ending that remarkable connection. There is a lot of controversy surrounding the book, and I beg you to read it so that we can discuss it... I really want to have that discussion.

The book, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years as a Slave and Four Years in the White House, is a fascinating read. It is FREE online... Please take the time...

The book, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years as a Slave and Four Years in the White House, is a fascinating read. It is FREE online... Please take the time...

and the kindle edition

is free.

http://www.amazon.com/Behind-Scenes-Thirty-years-slave-ebook/dp/B0082P4F7O/ref=sr_1_3?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1407469245&sr=1-3&keywords=elizabeth+keckley+behind+the+scenes

The last years of her life were difficult for Elizabeth. In 1892 she taught dressmaking and design at Wiberforce University; sadly, she had to resign after only one year - she had a stroke.

Although the records are sketchy, it is known that in May 1907 Elizabeth Keckley died in the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children in Washington, D.C.. Ironicly, it was an institution that was established using contributions from the Contraband Association founded by Elizabeth in 1862 to give support to recently freed slaves and returning civil war soldiers.

At the time of her death Elizabeth Keckley was 88 years old, and destitute.

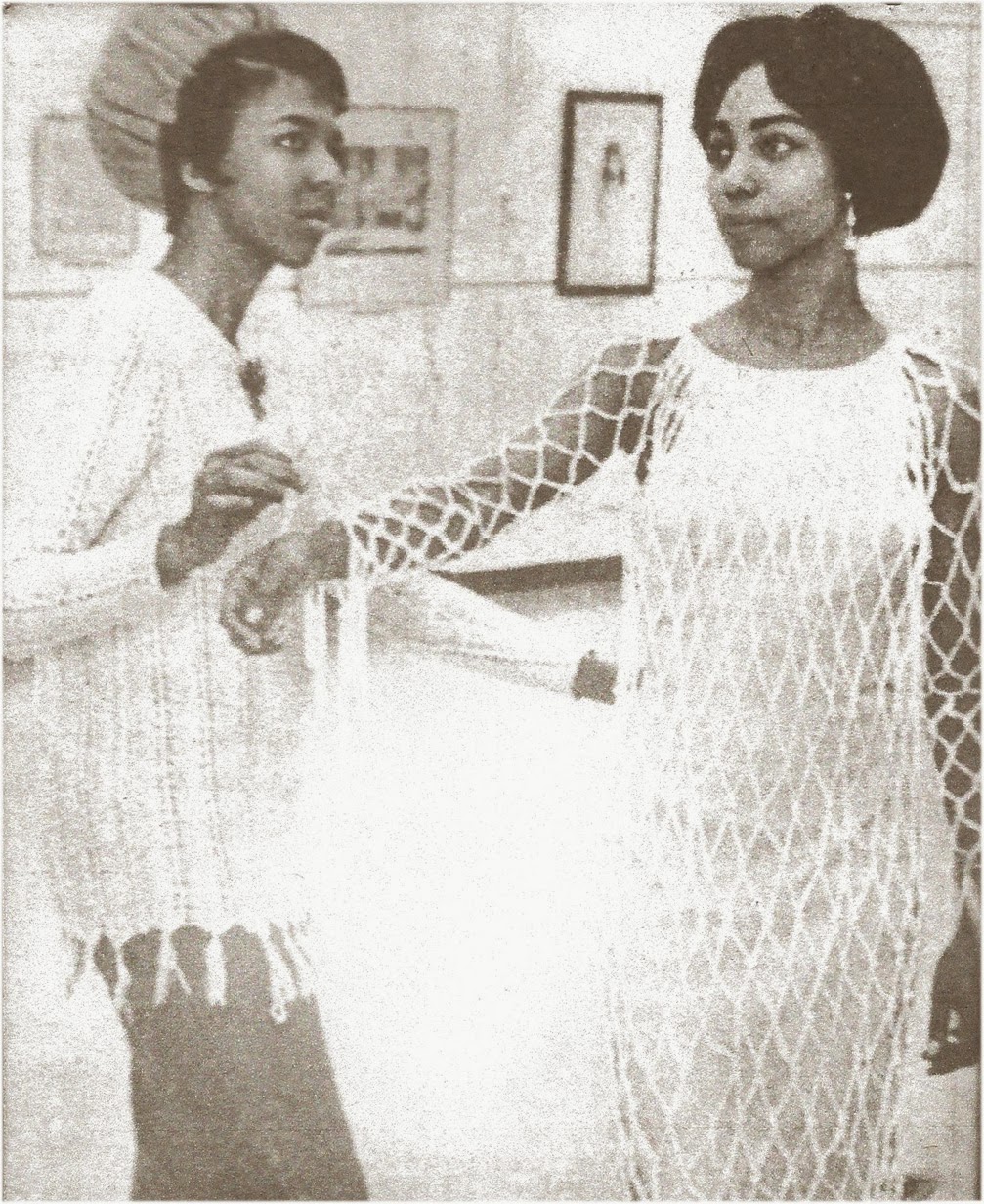

Mary Lincoln wearing an Elizabeth Keckley design in the 1850s. This is on display in the Smithsonian.

The last years of her life were difficult for Elizabeth. In 1892 she taught dressmaking and design at Wiberforce University; sadly, she had to resign after only one year - she had a stroke.

Although the records are sketchy, it is known that in May 1907 Elizabeth Keckley died in the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children in Washington, D.C.. Ironicly, it was an institution that was established using contributions from the Contraband Association founded by Elizabeth in 1862 to give support to recently freed slaves and returning civil war soldiers.

At the time of her death Elizabeth Keckley was 88 years old, and destitute.

Mary Lincoln wearing an Elizabeth Keckley design in the 1850s. This is on display in the Smithsonian.